Herpetology/Crocodilians and Turtles

This page contains information on members of Crocodylia and Testudines (Chelonia) on the Herpetology List. For more general information about the event, see Herpetology.

Order Crocodylia

There are 3 families of Crocodylia, with 23 species total. These families are:

- Gavialidae, containing 2 species, encompassing gharials and false gharials;

- Crocodylidae, containing 14 species in 3 genera, encompassing crocodiles; and

- Alligatoridae, containing 7 species in 4 genera, encompassing alligators and caimans.

| Etymology | Latinizing of the Greek κροκόδειλος (crocodeilos), which means both lizard and Nile crocodile. Crocodylia, as coined by Wermuth, in regards to the genus Crocodylus appears to be derived from the ancient Greek κρόκη (kroke)—meaning shingle or pebble—and δρîλος or δρεîλος (dr(e)ilos) for "worm". The name may refer to the animal's habit of basking on the pebbled shores of the Nile. |

|---|---|

| Physical Appearance | Crocodilians range in size from the Paleosuchus and Osteolaemus species, which reach 1–1.5 m (3 ft 3 in–4 ft 11 in), to the saltwater crocodile, which reaches 7 m (23 ft) and weighs up to 2,000 kg (4,400 lb), though some prehistoric species such as the late Cretaceous Deinosuchus were even larger at up to about 11 m (36 ft) and 3,450 kg (7,610 lb). They tend to be sexually dimorphic, with males much larger than females. Though there is diversity in snout and tooth shape, all crocodilian species have essentially the same body morphology. They have solidly built, lizard-like bodies with elongated, flattened snouts and laterally compressed tails. Their limbs are reduced in size; the front feet have five digits with little or no webbing, and the hind feet have four webbed digits and a rudimentary fifth. The skeleton is somewhat typical of tetrapods, although the skull, pelvis and ribs are specialised; in particular, the cartilaginous processes of the ribs allow the thorax to collapse during diving and the structure of the pelvis can accommodate large masses of food, or more air in the lungs. Both sexes have a cloaca, a single chamber and outlet at the base of the tail into which the intestinal, urinary and genital tracts open. It houses the penis in males and the clitoris in females. The crocodilian penis is permanently erect and relies on cloacal muscles for eversion and elastic ligaments and a tendon for recoil. The testes or ovaries are located near the kidneys. The eyes, ears and nostrils of crocodilians are at the top of the head. This allows them to stalk their prey with most of their bodies underwater. Crocodilians possess a tapetum lucidum which enhances vision in low light. While eyesight is fairly good in air, it is significantly weakened underwater. The fovea in other vertebrates is usually circular, but in crocodiles it is a horizontal bar of tightly packed receptors across the middle of the retina. When the animal completely submerges, the nictitating membranes cover its eyes. In addition, glands on the nictitating membrane secrete a salty lubricant that keeps the eye clean. When a crocodilian leaves the water and dries off, this substance is visible as "tears". The ears are adapted for hearing both in air and underwater, and the eardrums are protected by flaps that can be opened or closed by muscles. Crocodilians have a wide hearing range, with sensitivity comparable to most birds and many mammals. They have only one olfactory chamber and the vomeronasal organ is absent in the adults indicating all olfactory perception is limited to the olfactory system. Behavioural and olfactometer experiments indicate that crocodiles detect both air-borne and water-soluble chemicals and use their olfactory system for hunting. When above water, crocodiles enhance their ability to detect volatile odorants by gular pumping, a rhythmic movement of the floor of the pharynx. The well-developed trigeminal nerve allows them to detect vibrations in the water (such as those made by potential prey). The tongue cannot move freely but is held in place by a folded membrane. While the brain of a crocodilian is fairly small, it is capable of greater learning than most reptiles. Though they lack the vocal folds of mammals and the syrinx of birds, crocodilians can produce vocalisations by vibrating three flaps in the larynx. |

| Ecology, Habitat and Diet | Habitat: Amphibious.

Predators: Tend to be at the top of the food chain. Diet: Largely carnivorous. |

| Behavior and Locomotion | Locomotion: Crocodilians are excellent swimmers. During aquatic locomotion, the muscular tail undulates from side to side to drive the animal through the water while the limbs are held close to the body to reduce drag. When the animal needs to stop, steer, or manoeuvre in a different direction, the limbs are splayed out. Crocodilians generally cruise slowly on the surface or underwater with gentle sinuous movements of the tail, but when pursued or when chasing prey they can move rapidly. Crocodilians are less well-adapted for moving on land, and are unusual among vertebrates in having two different means of terrestrial locomotion: the "high walk" and the "low walk". Their ankle joints flex in a different way from those of other reptiles, a feature they share with some early archosaurs. One of the upper row of ankle bones, the astragalus, moves with the tibia and fibula. The other, the calcaneum, is functionally part of the foot, and has a socket into which a peg from the astragalus fits. The result is that the legs can be held almost vertically beneath the body when on land, and the foot can swivel during locomotion with a twisting movement at the ankle. Crocodilians, like this American alligator, can "high walk" with the limbs held almost vertically, unlike other reptiles. The high walk of crocodilians, with the belly and most of the tail being held off the ground, is unique among living reptiles. It somewhat resembles the walk of a mammal, with the same sequence of limb movements: left fore, right hind, right fore, left hind. The low walk is similar to the high walk, but without the body being raised, and is quite different from the sprawling walk of salamanders and lizards. The animal can change from one walk to the other instantaneously, but the high walk is the usual means of locomotion on land. The animal may push its body up and use this form immediately, or may take one or two strides of low walk before raising the body higher. Unlike most other land vertebrates, when crocodilians increase their pace of travel they increase the speed at which the lower half of each limb (rather than the whole leg) swings forward; by this means, stride length increases while stride duration decreases. Though typically slow on land, crocodilians can produce brief bursts of speed, and some can run at 12 to 14 km/h (7.5 to 8.7 mph) for short distances. A fast entry into water from a muddy bank can be effected by plunging to the ground, twisting the body from side to side and splaying out the limbs. In some small species such as the freshwater crocodile, a running gait can progress to a bounding gallop. This involves the hind limbs launching the body forward and the fore limbs subsequently taking the weight. Next, the hind limbs swing forward as the spine flexes dorso-ventrally, and this sequence of movements is repeated. During terrestrial locomotion, a crocodilian can keep its back and tail straight, since the scales are attached to the vertebrae by muscles. Whether on land or in water, crocodilians can jump or leap by pressing their tails and hind limbs against the substrate and then launching themselves into the air. |

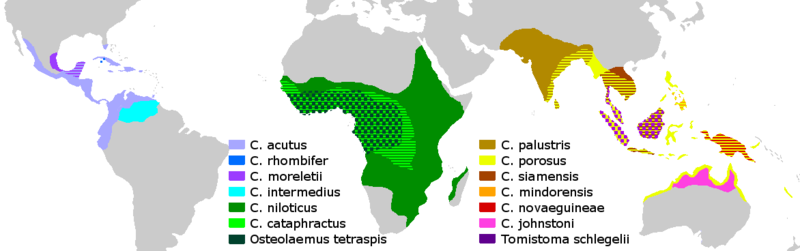

Family Crocodylidae (crocodiles)

Family Alligatoridae (alligators and caiman)

There are two extant species of alligator: Alligator mississippiensis (the American alligator) and A. sinensis (the Chinese/Yangtze alligator). There are six extant species of caiman: Caiman yacare (the Yacare caiman), C. crocodilus (the spectacled caiman), C. latirostris (the broad-snouted caiman), Melanosuchus niger (the black caiman), Paleosuchus palpebrosus (Cuvier’s dwarf caiman), and Paleosuchus trigonatus (the smooth-fronted caiman).

| Picture(s) |

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Etymology | From the Spanish el lagarto (the lizard). | ||||||||

| Physical Appearance | Aligators: Have a slow metabolism. Most of the muscle in jaw is evolved to bite and grip prey (muscles for closing are exceptionally powerful, and muscles for opening are very weak, able to be held shut using several rolls of duct tape for transportation). Gizzard stones often found in stomachs. Unidirectional movement of air through the lungs (like fish and birds) while most other amniotes have bidirectional/tidal breathing (air moves in one direction through the parabronchi, exits lung through inner branch, oxygen exchange takes place in extensive vasculature around the parabronchi). Have muscular, flat tails that propel them while swimming. Two kinds of white alligators are albino and leucistic: they are practically impossible to find in the wild and survive only in captivity (e.g. Aquarium of the Americas; New Orleans has leucistic alligators that were found in a Louisiana swamp in 1917). The Chinese alligator is fully armored (including the belly).

Differences from crocodiles: See #Family Crocodylidae (crocodiles) Size: Average adult American alligator weight is 360 kg (790 lb) up to over 450 kg (990 lb). Average height is 4.0 m (13.1 ft) up to 4.4 m (14 ft). The largest ever American alligator was found in Louisiana and was 5.84 m (19.2 ft) long. Average adult male Chinese alligator rarely weighs over 45 kg (99 lb) or exceeds 2.1 m (6.9 ft). Color: Black or dark olive-brown with white undersides (strongly contrasting white or yellow marks on juveniles which fade with age). Caimans: Scaly skin. Average maximum 6-40 kg (13-88 lb) except for M. niger, which can grow to 1100 kg (2400 lb) and 5 m (16 ft). P. palpebrosus grows to 1.2-1.5 m (3.9-4.9 ft). Differences between alligators and caimans: Caimans lack the bony septum between nostrils which alligators have, have ventral armor composed of overlapping bony scutes formed from two parts united by a suture, are relatively longer and more slender teeth, and have calcium rivets on scales that make hides stiffer and less valuable. | ||||||||

| Life Cycle | Adult life span not measured. An alligator at least 80 years old (named Muja) in Belgrade Zoo in Serbia brought from Germany in 1937 is the oldest alligator in captivity.

Eggs (summer): Female builds nest of vegetation (decomposition provides heat). Chinese alligators have the smallest eggs of any crocodilian. Sex of offspring fixed within 7-21 days of the start of the incubation (less than 30 degrees Celsius or 86 degrees Fahrenheit produces all females, and greater than 34 degrees Celsius or 93 degrees Fahrenheit produces all males). Nests constructed on leaves tend to be hotter (more males) than those constructed on wet marshes. Young: Baby alligators use egg teeth to get out of egg. Hatchlings have a ratio of five females to one male. Females weigh significantly more. The mother defends the nest from predators and assists hatchlings to water, providing protection for about a year if they remain in the area. Adult alligators regularly cannibalize younger individuals: after the outlawing of alligator hunting, populations quickly rebounded because of the higher rate of survival of juveniles. Female caimans build large nests (can be over 1.5 m wide) and lay 10-50 eggs which hatch in around 6 weeks. Females take their young to a shallow pool of water where they can learn how to hunt and swim. Mating season (late spring): Mature at length of 1.8 m (6 m). "Bellowing choruses" in April and May (large groups of animals bellow together for a few minutes a few times a day usually one to three hours after sunrise, accompanied by powerful blasts of infrasound). Males do a loud head-slap. Exhibit group courtship ("alligator dances") | ||||||||

| Ecology, Habitat and Diet | Effect on biodiversity: Increase plant diversity and provide habitats for other animals during drought by constructing alligator holes in wetlands. Feed on coypu and muskrats, which cause severe damage to wetlands through overgrazing. Keystone species in the Everglades.

Predators: Apex predator (may determine abundance of prey species like turtles and coypu). Caimans have few natural predators (humans are main predators). Jaguars and anacondas prey on smaller caiman species. Habitat: Alligators intolerant to salinity, ponds, marshes, wetlands, rivers, lakes, swamps, brackish environments. Diet: Eat foliage and fruit in addition to their usual diet of fish and meat. Young alligators eat small prey (e.g. fish, insects, snails, crustaceans, and worms) while mature alligators eat bigger prey (e.g. larger fish such as gar, turtles, mammals like coypu and muskrats, birds, deer, and other reptiles). Main diet is smaller animals that they can kill and eat in one bite. May kill larger prey by grabbing and dragging into the water to drown. Will consume carrion if hungry enough (larger ones known to ambush dogs, Florida panthers, and black bears). Consume bigger food through allowing it to rot or using a "death roll" (biting and then convulsing/spinning wildly until bite-sized chunks are torn off: tail flexing to a significant angle relative to body is crucial). Caimans hunt insects, birds, and small mammals and reptiles, in addition to a great deal of fish. | ||||||||

| Behavior and Locomotion | Less dangerous to humans than crocodiles (generally timid and tend to walk/swim away). Provoked into attack by people approaching alligators or alligator nests. Attacks are few but not unknown. Feeding alligators is illegal in Florida because eventually alligators will lose their fear of humans, which is a greater risk for both alligators and humans. Chinese alligator are the most docile of all crocodilians. Large males are solitary territorial. Smaller alligators are in larger numbers close to each other (have a high tolerance for alligators of similar size). Largest (both genders) defend prime territory. Caimans are fairly nocturnal.

Locomotion: Capable of short bursts of speed in very short lunges. Move on land through:

| ||||||||

| Conservation Status and Efforts | American alligator: Least Concern

Chinese alligator: Critically Endangered (IUCN Red List) with only a few dozen believed to be left in the wild (far fewer than in zoos). Chinese alligators are preserved by the Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge and Miami MetroZoo and are a CITES Appendix I species (extreme restrictions on trade and exportation). In 1999, there were an estimated 150 Chinese alligators left in the wild. Most remaining wild individuals live in the Anhui Chinese Alligator Nature Reserve. In danger from habitat pollution and reduction (because of rice paddies and poaching for medicinal purposes). Some are exterminated (some farmers consider them a threat). In 1979, Anhui Research Center for Chinese Alligator Reproduction was founded and had a breeding success, turning 200 to 10,000. The Changxing Nature Reserve and Breeding Center for Chinese Alligators housed almost 4,000 alligators. | ||||||||

| Distribution | Distributions for species of alligator and caiman:

| ||||||||

| Miscellaneous Information | Raised commercially for meat and skin (leather for luggage, handbags, shoes, belts, etc.). Helps with ecotourism. In 2010, the Archbishop of New Orleans ruled that alligator meat is considered fish for purposes of meat abstention. |

Order Testudines/Chelonia

| Alternate names | Turtles/tortoises/terrapins (depends on variety of English being used as all of these words can be used to describe specific type of chelonians) |

|---|---|

| Etymology | The word chelonian is popular among veterinarians, scientists, and conservationists working with these animals as a catch-all name for any member of the superorder Chelonia, which includes all turtles living and extinct, as well as their immediate ancestors. Chelonia is based on the Greek word for turtles, χελώνη chelone, Testudines, on the other hand, is based on the Latin word for tortoise, testudo. Terrapin comes from an Algonquian word for turtle. Differences exist in usage of the common terms turtle, tortoise, and terrapin, depending on the variety of English being used; usage is inconsistent and contradictory. These terms are common names and do not reflect precise biological or taxonomic distinctions. The American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists uses "turtle" to describe all species of the order Testudines, regardless of whether they are land-dwelling or sea-dwelling, and uses "tortoise" as a more specific term for slow-moving terrestrial species. General American usage agrees; turtle is often a general term (although some restrict it to aquatic turtles); tortoise is used only in reference to terrestrial turtles or, more narrowly, only those members of Testudinidae, the family of modern land tortoises; and terrapin may refer to turtles that are small and live in fresh and brackish water, in particular the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). In America, for example, the members of the genus Terrapene dwell on land, yet are referred to as box turtles rather than tortoises. British usage, by contrast, tends not to use "turtle" as a generic term for all members of the order, and also applies the term "tortoises" broadly to all land-dwelling members of the order Testudines, regardless of whether they are actually members of the family Testudinidae. In Britain, terrapin is used to refer to a larger group of semi-aquatic turtles than the restricted meaning in America. Australian usage is different from both American and British usage. Land tortoises are not native to Australia, yet traditionally freshwater turtles have been called "tortoises" in Australia. Some Australian experts disapprove of this usage—believing that the term tortoises is "better confined to purely terrestrial animals with very different habits and needs, none of which are found in this country"—and promote the use of the term "freshwater turtle" to describe Australia's primarily aquatic members of the order Testudines because it avoids misleading use of the word "tortoise" and also is a useful distinction from marine turtles. |

| Physical Appearance | The largest living chelonian is the leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), which reaches a shell length of 200 cm (6.6 ft) and can reach a weight of over 900 kg (2,000 lb). Freshwater turtles are generally smaller, but with the largest species, the Asian softshell turtle Pelochelys cantorii, a few individuals have been reported up to 200 cm (6.6 ft). This dwarfs even the better-known alligator snapping turtle, the largest chelonian in North America, which attains a shell length of up to 80 cm (2.6 ft) and weighs as much as 113.4 kg (250 lb). Giant tortoises of the genera Geochelone, Meiolania, and others were relatively widely distributed around the world into prehistoric times, and are known to have existed in North and South America, Australia, and Africa. They became extinct at the same time as the appearance of man, and it is assumed humans hunted them for food. The only surviving giant tortoises are on the Seychelles and Galápagos Islands and can grow to over 130 cm (51 in) in length, and weigh about 300 kg (660 lb). The largest ever chelonian was Archelon ischyros, a Late Cretaceous sea turtle known to have been up to 4.6 m (15 ft) long. The smallest turtle is the speckled padloper tortoise of South Africa. It measures no more than 8 cm (3.1 in) in length and weighs about 140 g (4.9 oz). Two other species of small turtles are the American mud turtles and musk turtles that live in an area that ranges from Canada to South America. The shell length of many species in this group is less than 13 cm (5.1 in) in length. The main internal organs of these reptiles are the lungs, heart, stomach, liver, intestines, and the urinary bladder. A cloaca serves both excretory and reproductive functions. Turtles have a complete skeletal system with partially webbed feet.

Neck retraction: Turtles are divided into two groups, according to how they retract their necks into their shells (something the ancestral Proganochelys could not do). The Cryptodira retract their necks backwards while contracting it under their spine, whereas the Pleurodira contract their necks to the side. Head: Most turtles that spend most of their lives on land have their eyes looking down at objects in front of them. Some aquatic turtles, such as snapping turtles and soft-shelled turtles, have eyes closer to the top of the head. These species of turtle can hide from predators in shallow water, where they lie entirely submerged except for their eyes and nostrils. Near their eyes, sea turtles possess glands that produce salty tears that rid their body of excess salt taken in from the water they drink. Turtles have rigid beaks and use their jaws to cut and chew food. Instead of having teeth, which they appear to have lost about 150-200 million years ago, the upper and lower jaws of the turtle are covered by horny ridges. Carnivorous turtles usually have knife-sharp ridges for slicing through their prey. Herbivorous turtles have serrated-edged ridges that help them cut through tough plants. They use their tongues to swallow food, but unlike most reptiles, they cannot stick out their tongues to catch food. Shell: Upper shell is carapace, lower shell is plastron, carapace and plastron are joined together by bridges, inner layer of shell made up of about 60 bones (that include portions of the backbone and the ribs, meaning the turtle cannot crawl out of its shell), outer layer of shell of most turtles is covered by horny scales called scutes that are part of its outer skin (epidermis) made of keratin, scutes overlap seams between shell bones and add strength to the shell, leatherback sea turtle and soft-shelled turtles have shells covered with leathery skin instead of horny scutes, rigid shell prevents turtles from breathing as other reptiles do (by changing the volume of their chest cavities via expansion and contraction of the ribs), adapted to lifestyle, commonly colored brown, black, or olive green (may have red, orange, yellow, or grey markings, often spots, lines, or irregular blotches in some species), land-based tortoises have much heavier shells than aquatic and soft-shelled turtles which need to avoid sinking in water and swim faster with more agility, lighter shells have large spaces called fontanelles between the shell bones, leatherback sea turtle shells are extremely light because they lack scutes and contain many fontanelles pH buffer: Suggested by Jackson (2002) that the turtle shell can function as pH buffer, turtles use two general physiological mechanisms when they must endure through anoxic conditions (e.g. during winter periods trapped beneath ice or within anoxic mud at the bottom of ponds), turtle shell both releases carbonate buffers and uptakes lactic acid Breathing: (1) Employ limb pumping, sucking air into their lungs and pushing it out by moving the limbs in and out relative to the shell and (2) when the abdominal muscles that cover the posterior opening of the shell contract, the pressure inside the shell and lungs decreases, drawing air into the lungs, allowing these muscles to function like the mammalian diaphragm; a second set of abdominal muscles face the opposite way and when they contract they expel air under positive pressure Skin and molting: As mentioned above, the outer layer of the shell is part of the skin; each scute (or plate) on the shell corresponds to a single modified scale. The remainder of the skin has much smaller scales, similar to the skin of other reptiles. Turtles do not molt their skins all at once as snakes do, but continuously in small pieces. When turtles are kept in aquaria, small sheets of dead skin can be seen in the water (often appearing to be a thin piece of plastic) having been sloughed off when the animals deliberately rub themselves against a piece of wood or stone. Tortoises also shed skin, but dead skin is allowed to accumulate into thick knobs and plates that provide protection to parts of the body outside the shell. By counting the rings formed by the stack of smaller, older scutes on top of the larger, newer ones, it is possible to estimate the age of a turtle, if one knows how many scutes are produced in a year. This method is not very accurate, partly because growth rate is not constant, but also because some of the scutes eventually fall away from the shell. Limbs: Terrestrial tortoises have short, sturdy feet. Tortoises are famous for moving slowly, in part because of their heavy, cumbersome shells, which restrict stride length. Amphibious turtles normally have limbs similar to those of tortoises, except that the feet are webbed and often have long claws. These turtles swim using all four feet in a way similar to the dog paddle, with the feet on the left and right side of the body alternately providing thrust. Large turtles tend to swim less than smaller ones, and the very big species, such as alligator snapping turtles, hardly swim at all, preferring to walk along the bottom of the river or lake. As well as webbed feet, turtles have very long claws, used to help them clamber onto riverbanks and floating logs upon which they bask. Male turtles tend to have particularly long claws, and these appear to be used to stimulate the female while mating. While most turtles have webbed feet, some, such as the pig-nosed turtle, have true flippers, with the digits being fused into paddles and the claws being relatively small. These species swim in the same way as sea turtles do (see below). Sea turtles are almost entirely aquatic and have flippers instead of feet. Sea turtles fly through the water, using the up-and-down motion of the front flippers to generate thrust; the back feet are not used for propulsion but may be used as rudders for steering. Compared with freshwater turtles, sea turtles have very limited mobility on land, and apart from the dash from the nest to the sea as hatchlings, male sea turtles normally never leave the sea. Females must come back onto land to lay eggs. They move very slowly and laboriously, dragging themselves forwards with their flippers. |

| Life Cycle | Parents usually do not help young or care for eggs. Sex of young is usually temperature dependent. |

| Ecology, Habitat and Diet | Although many turtles spend large amounts of their lives underwater, all turtles and tortoises breathe air and must surface at regular intervals to refill their lungs.

Diet: A turtle's diet varies greatly depending on the environment in which it lives. Adult turtles typically eat aquatic plants; invertebrates such as insects, snails, and worms; and have been reported to occasionally eat dead marine animals. Several small freshwater species are carnivorous, eating small fish and a wide range of aquatic life. However, protein is essential to turtle growth and juvenile turtles are purely carnivorous. Sea turtles typically feed on jellyfish, sponge, and other soft-bodied organisms. Some species of sea turtle with stronger jaws have been observed to eat shellfish while some species, such as the green sea turtle, do not eat any meat at all and, instead, have a diet largely made up of algae. |

| Behavior and Locomotion | Senses: Turtles are thought to have exceptional night vision due to the unusually large number of rod cells in their retinas. Turtles have color vision with a wealth of cone subtypes with sensitivities ranging from the near ultraviolet (UVA) to red. Some land turtles have very poor pursuit movement abilities, which are normally found only in predators that hunt quick-moving prey, but carnivorous turtles are able to move their heads quickly to snap.

Communication: While typically thought of as mute, turtles make various sounds when communicating. Tortoises may be vocal when courting and mating. Various species of both freshwater and sea turtles emit numerous types of calls, often short and low frequency, from the time they are in the egg to when they are adults. These vocalizations may serve to create group cohesion when migrating. Intelligence: It has been reported that wood turtles are better than white rats at learning to navigate mazes. Case studies exist of turtles playing. They do, however, have a very low encephalization quotient (relative brain to body mass), and their hard shells enable them to live without fast reflexes or elaborate predator avoidance strategies. In the laboratory, turtles (Pseudemys nelsoni) can learn novel operant tasks and have demonstrated a long-term memory of at least 7.5 months. |

| Conservation Status and Efforts | Nearly all species of sea turtle are endangered (poached and over-exploited for eggs, meat, skin, and shells; habitat destruction; accidental capture in fishing gear). |

| Miscellaneous Information | A group of turtles is known as a bale. The Eocene epoch (59-33.9 mya) was seemingly the golden age for turtle diversity. |

Family Chelydridae (snapping turtles)

Chelydridae belongs to the suborder Cryptodira and has two extant genera, Chelydra and Macrochelys. Chelydra has three species: C. serpentina (the common snapping turtle), C. acutirostris (the South American snapping turtle), and C. rossignonii (the Central American snapping turtle). Macrochelys has anywhere from one to three extant species, M. suwanniensis (the Suwannee snapping turtle, previously though to be part of M. teminckii), M. teminckii (the alligator snapping turtle), and M. apalachicolae (the Apalachicola snapping turtle, which is not generally recognized as a different species from M. teminckii).

| Etymology | C. rossignonii is in honor of the French-born coffee grower Jules Rossignon. M. temminckii is in honor of Dutch zoologist Coenraad Jacob Temminck. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Appearance | Common snapping turtles: Powerful beak-like jaws. Highly mobile head and neck (origin of the specific name serpentina). Can bite handler even if picked up from the side of the shell or hind legs. Sharp claws (like dog claws except they cannot be trimmed). Claws are used for digging and gripping, not attacking—the legs are not strong enough for a swiping motion—or eating—no opposable thumbs. Rugged muscular build. Ridged carapace, usually 25-47 cm (9.8-18.5 inches) in adults. Usually weigh 4.5-16 kg (9.9-35.3 lb). The heaviest caught in the wild was 34 kg (75 lb). The heaviest native freshwater turtle in the north. Plastra are around 22.5 cm (8.9 inches) long, and almost all common snapping turtles that weigh over 10 kg (22 lb) are old males. They continue to grow throughout life and have snorkel-like nostrils positioned on the top of the snout. The have large heads relative to their bodies, broad and flat carapaces, cruciform plastra (giving them more efficient leg movement for walking along the bottom of ponds and streams), and the longest tails of any turtle.

Alligator snapping turtles: One of the heaviest freshwater turtles in the world. Large heavy heads and long, thick shells with three dorsal ridges of large scales (osteoderms) making them appear like an ankylosaurs. Solid grey/brown/black/olive-green and usually covered in algae. Radiating yellow patterns around eyes that break up outlines of eyes and keep turtles camouflaged. Star-shaped arrangement of fleshy, filamentous "eyelashes". In 1937, an alligator snapping turtle weighing 183 kg (403 lb) was found in Kansas (not verified). They continue to grow throughout life and are generally 8.4-80 kg (19-176 lb) and 35-80.8 cm (13.8-31.8 in). Males are typically larger, and specimens over 45 kg (99 lb) are generally very old males. Only the giant softshell turtles of Chitra, Rafetus, and Pelochelys reach a comparable size. The male’s cloaca extends beyond the carapace edge while the female’s is at the carapace edge or nearer to the plastron. The male’s tail is thicker at the base because of the reproductive organs. The inside of the mouth camouflaged with a vermiform (worm-shaped) appendage on the tip of the tongue used to lure fish (Peckhamian mimicry). Alligator snapping turtles have a bite force about the same level as humans relative to size (158 plus or minus 18 kgf, 1550 plus or minus 180 Newtons, or 348 plus or minus 40 lbf). They can still bite through handle of a broom but rarely can bite human fingers clean off. They have four marginal scutes (unlike C. serpentina). | ||||||||

| Life Cycle | High and variable mortality of embryos and hatchlings. Delayed sexual maturity. Extended adult longevity. Iteroparity (repeated reproductive events). Low reproductive success per reproductive event.

Common snapping turtles: Females mature later at a larger size (15-20 years) in northern populations compared to southern populations (12 years). Maximum age of over 100 years. Eggs are vulnerable to crows, minks, skunks, foxes, and raccoons. They are laid in sandy soil some distance from the water. Females lay 25-80 eggs each year, guiding the eggs into the nest using the hind feet and covering the nest with sand for incubation and protection. Incubation period is temperature dependent (8 to 18 weeks). Eggs overwinter in the nest in cooler climates. Hatchlings are vulnerable to the aforementioned predators as well as herons (mostly great blue herons), bitterns, hawks, owls, fishers, bullfrogs, large fish, and snakes. Mate from April to November (peak June and July). Females can hold sperm for several seasons. Alligator snapping turtles: Believed to be able to live to 1200 (although 80-120 is more likely). Typically live between 20 and 70 years in captivity. Mature at around 12 years, with a size of around 8 kg (18 lb) and 33 cm (13 in). Mate yearly (early spring in the south and later spring in the north). | ||||||||

| Ecology, Habitat and Diet | Habitat: Freshwater – common snapping turtles prefer shallow ponds and streams (some in brackish environments such as estuaries) and are extremely cold tolerant, remaining active under ice during winter and capable to diving to over 2-3 meters.. They come on land only to lay eggs.

Predators: Large, old, male common snapping turtles are at the top of their food chain. C. serpentina adults are sometimes ambushed by northern river otters during hibernation. Reported predators are coyotes, black bears, alligators and larger cousins, and alligator snapping turtles. Diet: The common snapping turtle consume both animal and plant matter and is an important aquatic scavenger. Common snapping turtles are also active hunters that prey on anything they can swallow (e.g. invertebrates, fish, frogs, other reptiles like snakes and smaller turtles, unwary birds, and small mammals), which can be detrimental to breeding waterfowl since they will occasionally take ducklings and goslings. They are a somewhat flatulent species due to their varied diet. The alligator snapping turtle is also opportunistic and almost entirely carnivorous, relying on catching food and scavenging. Alligator snapping turtles will eat anything they can catch and target abundant and easily caught prey, e.g. fish, fish carcasses, molluscs, carrion, and amphibians. They are also known to eat snakes, crayfish, worms, water birds, aquatic plants, and other turtles and on occasion prey on aquatic rodents like nutria and muskrats or even small mammals like squirrels, opossums, raccoons, and armadillos. | ||||||||

| Behavior and Locomotion | C. serpentina is combative when out of water. It will make a hissing sound and release a musky odor when stressed. It is likely to hide itself under sediment when in water. Common snapping turtles sometimes bask by floating on surface with only the carapace exposed. They also bask on fallen logs in early spring in the north and may lie beneath a muddy bottom with only the head exposed in shallow waters (stretching their long necks to the surface for an occasional breath). If an unfamiliar species is encountered (such as humans), they may become curious and survey the situation (rarely may bump their nose on a person’s leg) if an unfamiliar species is encountered. Travel extensively over land to reach new habitats (can be driven to move by pollution, habitat destruction, food scarcity, overcrowding, etc.) or to lay eggs. Hibernating snapping turtles do not breathe for (in the northern region) more than six months. They can get oxygen by pushing their head out of the mud and allowing gas exchange between mouth membranes and throat membranes (extrapulmonary respiration). They utilize anaerobic pathways if there is not enough oxygen to burn sugars and fat. However, there is an undesirable side-effect from this process that comes in spring known as oxygen debt.

M. temminckii hunts diurnally by keeping its mouth open and imitating the motions of a worm using its tongue (the mouth is then closed with tremendous force and speed). Younger turtles catch minnows this way while larger turtles must catch more food more actively. There are no reported human deaths by alligator snapping turtles, and they are not prone to biting. They most often hunts at night, and adults have been known to kill and eat small American alligators. Locomotion: Moving sideways is significant slower. They are capable of swimming up, swimming down, and walking. | ||||||||

| Conservation Status and Efforts | Least concern: however, their life history is sensitive to disruption by human activity (target for surveys, ID of major habitats, investigation and mitigation of threats, education of public including landowners, etc. from governmental departments, universities, museums, and citizen science projects). M. temminckii is a threatened species (CITES III limits exportation from the US and international trade) and is protected by state law in Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois, and Missouri, as well as labeled “in need of conservation” in Kansas. | ||||||||

| Distribution | Distribution by species:

| ||||||||

| Miscellaneous Information | It is a misconception that snapping turtles can be picked up safely by the tail (doing so will harm the turtle’s tail and vertebral column). Trying to rescue a snapping turtle by getting it to bite a stick and then dragging it out of danger will severely scrape the legs and underside of the turtle (leading to deadly infections). The safest way to pick up a snapping turtle is using a shovel or gasping the carapace above the back legs or picking up the corners of a blanket or tarp with the turtle in the middle. They are raised on some turtle farms in China. Common snapping turtles may be invasive in Italy and Japan from unwise exotic pet releases. Snapping turtles are a traditional ingredient in turtle soup (however, this may be toxic due to bioaccumulation). They are sometimes captive bred as an exotic pet; however, they do not make good pets – hand feeding is dangerous, and extreme temperatures result in the turtle refusing to eat. It is illegal to keep M. temminckii as a pet in California (where alligator snapping turtles do not naturally occur). Alligator snapping turtles were released into Czech Republic and Germany. Four were caught in Bohemia, and they are considered an invasive species in Oregon (where one was captured and euthanized in October 2013 in the Prineville Reservoir). |

Family Kinosternidae (musk and mud turtles)

Kinosternidae belongs to the suborder Cryptodira and is split into two subfamilies, Kinosternon (consisting of subfamilies Kinosternoninae – with Kinosternon spp., the mud turtles, and Sternotherus spp., the musk turtles – and Staurotypinae – with Claudius angustatus, the narrow-bridged musk turtle and Staurotypus spp., the Mexican/giant/three-keeled/cross-breasted musk turtles). Staurotypinae may be better as a separate family (Staurotypidae). There are 24+ species.

Musk and mud turtles are also called kinosternids (alluding to the familial name). They are close relatives to Chelydridae, the snapping turtles.

| Alternate names | Musk turtles are also known as stinkpots. |

|---|---|

| Etymology | Musk turtles are capable of releasing a foul-smelling musk from their Rathke’s glands, most similar to those of snapping turtles, under the rear of shells when disturbed. Some species also release foul-smelling secretions from the cloaca. |

| Physical Appearance | Size: Most are small, reaching 10-15 cm or 3.9-5.9 in SCL. Sternotherus spp. can be the smallest turtles, growing to 8-14 cm (3.1-5.5 in) while Staurotypus spp. can grow to 30 cm (12 in) and have large heads. C. angustatus turtles generally grow to 16.5 cm (6.5 in). Old individuals have especially large heads.

Distinguishing features: Have highly domed carapaces with distinct keels down the center. Sexual dimorphism: Females are significantly larger while males have much longer tails. Color: Various, ranging between black, brown, green, and yellowish. Some have a distinctive yellow striping along the sides of the head and neck. Most have no shell markings. Some species have radiating black markings on each carapace scute. Shell: Hindlimbs are mostly invisible when the turtle is at rest. The plastron is hinged in some species (allowing them to wholly enclose their limbs, neck, and tail inside their shells). The carapace is usually solid, lacking the hinges and mobile/flexible zones present in some turtles. Have oblong and moderately domed carapaces. Plastron ranges from reduced to covering the whole shell, with fewer than 10 epidermal marginal scutes. Musk turtles have small and cruciform plastra that give them more efficient leg movement for walking along the bottom of ponds and streams. Staurotypus spp. turtles have plastra of only seven or eight scutes. Genus differences: Mud turtles are generally smaller than musk turtles and do not have as highly domed carapaces. Three-keeled musk turtles have yellow undersides with brown, black, or green bodies and have three distinctive keels that run their length (hence the name). Narrow-bridged musk turtles are typically brown with wood-like scutes (in terms of lines and graining) and often have bright-yellow markings (algae often heavily covers these color markings as they age). They have extremely narrow bridges, such that they can rotate their plastra independently of their carapaces and such broad and narrow heads that they cannot be retracted into the shell. Barbels present on the chins and throats of some Sternotherus species. S. depressus turtles (flattened musk turtles) have relatively wide and flat shells, which may be an adaptation for hiding in crevices along the banks in which they live. Mud turtles lack endoplastra. |

| Life Cycle | Breed in late spring and early summer. Lay around four hard-shelled eggs (sometimes 1 or 2 huge eggs, sometimes 10 or more tiny eggs). Some species overwinter in subterranean nests (emerging the following spring). Some adults spend winter on land (constructing burrows with small air holes used on warm days). Ranges from female-dominated to male-dominated sexual size dimorphism. Some produce a single clutch in the spring while some nest multiple times in the summer and some nest nearly year-round. Sex determination ranges from genetic with sex chromosomes to temperature-dependent. Embryonic development is direct in some species whereas other species exhibit early embryonic diapause and/or late embryonic estivation. Incubation periods range from 56 to over 366 days. |

| Ecology, Habitat and Diet | Habitat: Freshwater aquatic systems (slow moving bodies of water, often with soft, muddy bottoms and abundant vegetation). Some species inhabit highly seasonal ephemeral ponds which may only contain water for a few months of each year. Range from north temperate to tropical and rainforest to grasslands to desert. Brumate on land. Can forage on land. Occupy underground retreats/communal nests. Occasionally nest below vegetation.

Predators: Racoons eat the eggs of Kinosternon subrubrum (the Eastern/common mud turtle) while herons and alligators often hunt the adults. Diet: Carnivores. Feed mainly on mollusks (snails and clams), crustaceans, insects, annelids, small fish (usually as fresh carrion), and even small carrion. Some are highly specialized mollusk feeders and eat little else. Some also eat algae and the seeds and leaves of certain plants. Grab and crush hard-shelled prey. |

| Behavior and Locomotion | The yellow mud turtle (Kinosternon flaviscens) is the only species of turtle suspected to exhibit parental care (studies in Nebraska suggest that the females sometimes stay with the nest and may urinate on the eggs long after laying them, either to keep them moist or to protect them from snake predation by making them less palatable). Sternotherus spp. are highly aquatic. However, the common musk turtle is known to bask on fallen trees and coarse woody debris on shorelines. Musk turtles are almost entirely aquatic, spending much of their time walking along the bottom, foraging for food. They are often nocturnal. C. angustatus is a ferocious biter. Some kinosternids can undergo submerged and fully aquatic respiration. Some can estivate underground for up to two years.

Locomotion: Capable of limited climbing and will sometimes ascend steep slopes or sloping branches or logs, sometimes falling onto boats from overhanging branches or fallen trees. |

| Conservation Status and Efforts | Most Kinosternidae species are common, reaching amazing population densities (as high as 1,200 per 2.5 acres [1 ha]). However, two tropical, one subtropical, and one temperate species are listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. The two tropical species (K. dunni and K. angustipons) are lowland forms with very restricted ranges and hence are probably affected most negatively by habitat destruction. The subtropical species (K. sonoriense) lives primarily in permanent water systems in the deserts of the U.S. Southwest; human competition for water resources has eliminated most of the habitat for this species. K. subrubrum is exploited by the pet trade and listed as an endangered species in Indiana. The temperate species (Sternotherus depressus) also has a restricted distribution in the permanent streams of north-central Alabama; habitat destruction associated with coal mining and forest clear-cutting seems to have caused the declines in this species. |

| Distribution | Musk turtle: North and South America (Sternotherus spp. in southern Canada, US, and Mexico; Staurotypus spp. in Mexico and Central America, Claudius spp. in Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize)

Mud turtle: US, Mexico, Central America, South America (great species richness in Mexico, only three species in South America) |

| Miscellaneous Information | Sternotherus odoratus (the common musk turtle/stinkpot) is the most common species of Sternotherus in North America. Kinosternids do not have a good fossil record. |

Family Emydidae (box, pond, and marsh turtles)

Genus Terrapene (box turtles)

Terrapene belongs to subfamily Emydinae and is comprised of 12 taxa and 4 species (T. carolina, the common box turtle, T. coahuila, the Coahuilan/aquatic box turtle, T. nelsoni, the spotted box turtle, and T. ornata, the western/ornate box turtle). Terrapene was coined by Merrem in 1820 as a genus separate from Emys for those species that had a sternum separated into two or three divisions and that could move these parts independently. The Asian box turtle belongs to a separate genus, Cuora.

| Etymology | Terrapene is derived from the Algonquin for turtle. English writers in 1834 referred to them as box-tortoises from their resemblance to tightly closed boxes when the head, tail, and legs are drawn in. |

|---|---|

| Physical Appearance | Has a domed shell which is hinged at the bottom (allowing it to close its shell tightly to escape predators). |

| Life Cycle | Chance of death seems not to increase with age after maturity is reached. Average lifespan of 50 years. Significant portion live over 100 years. Growth directly affected by amount of food, type of food, water, illness, et cetera. Age cannot be estimated by counting growth rings on scutes. Eggs are flexible and oblong (on average 2-4 cm or 1-2 in and 5-11 g or 0.2-0.4 oz). Normal clutch size of 1-7 eggs. Average clutch size is larger in more northern populations while southern and captive box turtles have more than one clutch per year. Risk of death is greatest in small individuals due to size and weaker carapace and plastron. Many hatchlings die during their first winter. Adult shells are seldom fractured but still vulnerable to surprise attacks and persistent gnawing/pecking. |

| Ecology, Habitat and Diet | Habitat: Wide variety (varies on a day-to-day, season-to-season, and species-to-species basis). Generally mesic woodlands (moderate/well-balanced supply of moisture). T. ornata is the only species regularly found in grasslands. The desert box turtle T. o. luteola is found in semideserts (rainfall predominantly in summer). The Coahuilan box turtle T. coahuila is found in a 360 square-km region characterized by marshes, permanent presence of water, and several types of cacti.

Predators: Commonly mammals such as minks, skunks, raccoons, dogs, and rodents. Also can be killed by birds (e.g. crows and ravens) and snakes (e.g. racers and cottonmouths). Diet: Omnivores with a varied diet. Basically eat anything they can catch. Mostly invertebrates (e.g. insects, earthworms, and millipedes) as they are plentiful and easy to catch but also 30-90% vegetation. Also eat fruits (e.g. cacti, apples, and several species of berry) and gastropods (e.g. Heliosoma and Succinea). Speculated that for the first 5-6 years they are primarily carnivorous and adults are primarily herbivorous, but there is no scientific basis for such a difference. Box turtles have been reported eating birds and small rodents that were trapped or had already died. Some species will eat poisonous mushrooms on a regular basis, making them poisonous to predators. |

| Behavior and Locomotion | Defend from predators by hiding, closing the shell, and biting. Tend to move farther into woods prior to hibernation, where they dig a chamber for overwintering. Ornate box turtles dig chambers of up to 50 cm. Eastern box turtles become dormant at a depth of about 10 cm. Location of overwintering can be up to 0.5 km from the summer habitat and is often in close proximity to the previous year's. Active year-round in more southern locations as observed in T. coahuila and T. carolina major. Other box turtles in hotter locations are more active (T. carolina yukatana) or only active during the wet seasons. |

| Conservation Status and Efforts | T. coahuila is endemic to Coahuila and classified as endangered (range reduced by 40% in past 40-50 years; population reduced from well over 10000 to 2500 in 2002). T. carolina is the most widely distributed and classified as vulnerable. T. ornata is near threatened. T. nelsoni has insufficient information.

Efforts and concerns: Sniffer dogs have been trained to find and track box turtles as part of conservation efforts. It is recommended to buy captive bred box turtles (in the regions where this is allowed) to reduce pressure put on wild populations. A 3-year study in Texas found that over 7000 box turtles were taken from the wild for commercial trade and a similar study in Louisiana found that in a 41-month period, nearly 30000 box turtles were taken from the wild for resale, many for export to Europe. Turtles once captured are often kept in poor conditions where up to half of them die. Those living long enough to be sold may suffer from conditions such as malnutrition, dehydration, and infection. Indiana, Tennessee, and other states prohibit collecting wild turtles. Many states require a permit to keep them. Breeding is prohibited in some states for fear of its possible detrimental effects upon wild populations. Box turtles have a low reproduction rate, intensifying the negative impact of collecting box turtles from the wild. |

| Distribution | The Coahuila box turtle is found only in the Cuatro Ciénegas Basin in Coahuila, Mexico. |

| Miscellaneous Information | Box turtles do not make good pets for small children. They are easily stressed by over-handling, require more care than generally thought, get stressed when moved into new surroundings, may wander aimlessly until they die trying to find their original home, and can carry Salmonella. The three-toed box turtles (T. carolina triunguis) are often considered the best box turtles to keep as pets since they are hardy and seem to suffer less when moved into a new environment. Box turtles require an outdoor enclosure and consistent exposure to the sun and a varied diet; otherwise, growth can be stunted and the immune system can be injured. Box turtles appeared abruptly in the fossil record (essentially in modern form), which may indicate that they are a generalist species (able to thrive in a wide variety of environmental conditions and can make use of a variety of different resources) as opposed to a specialist species. It is complicated to establish how evolution from other turtles took place. The oldest fossils were found in Nebraska (15 mya in the Miocene) and resemble the aquatic box turtle. T. ornata and T. carolina fossils date from 5 mya. The only recognized extinct subspecies, T. carolina putnami, dates from the Pliocene (5.33-2.58 mya) and had a carapace length of 30 cm (12 in) which is much larger than other species. Box turtles are the official state reptiles of four states (North Carolina and Tennessee honor T. carolina carolina, the eastern box turtle while Missouri honors T. carolina triunguis, the three-toed box turtle, and Kansas honors T. ornata, the ornate box turtle). Pennsylvania almost named the eastern box turtle as the state reptile (passed through one house of legislature). |

Genus Actinemys (western pond turtles)

Actinemys belongs to the subfamily Emydinae and has one species, A. marmorata. The taxonomy of the western pond turtle is currently under debate; at present, the IUCN Red List recognises that the western pond turtle belongs in its own genus. However, there is deliberation that it may belong to the genus Emys which is composed of the European pond turtle (E. orbicularis), the Sicilian pond turtle (E. trinacris), and Blanding’s turtle (E. blandingii) which may belong in a separate genus itself (Emydoidea). There were previously thought to be two subspecies of the western pond turtle: the southern western pond turtle (A. m. pallida) and the northern western pond turtle (A. m. marmorata), but now there is evidence for four separate groups, which do not match the distribution of the earlier described subspecies.

| Alternate names | Pacific pond turtle, Emys marmorata, Clemmys marmorata |

|---|---|

| Etymology | The specific name marmorata refers to the marbled pattern of both the soft parts and carapace. |

| Physical Appearance | Color: The carapace is usually light to dark brown or dull olive, either with no pattern or with an attractive pattern of fine, dark radiating lines on the scutes. The plastron is yellowish, sometimes with dark blotches in the centers of the scutes. The limbs and head are olive, yellow, orange, or brown, often with darker flecks or spots.

Size: The shell is 11-21 cm (4.5-8.5 in) in length. The carapace is low and broad, usually widest behind the middle. Adult carapaces are smooth, lacking a keel or serrations. Sexual dimorphism: In males, the cloaca is positioned beyond the edge of the plastron, whereas in females, it does not reach the edge of the plastron. Males have a yellow or whitish chin and throat, a flatter carapace, a more concave plastron, and a more pointed snout than females. |

| Life Cycle | Thought to live for up to 40 years. May survive more than 50 years in the wild.

Hatchlings: Hatchlings from northern California northward overwinter in the nest, which may explain the difficulty researches have had in trying to locate hatchlings in the fall months. Winter rains may be necessary to loosen the hardpan soil where some nests are deposited. It may be that the nest is the safest place for hatchlings to shelter while they await the return of warm weather. Whether it is hatchlings or eggs that overwinter, young first appear in the spring following the year of egg deposition. Western pond turtles develop slowly in areas with short or cool summers, taking up to eight years to reach sexual maturity (may even be 10-12 years). They can grow relatively fast in warmer regions and in some nutrient-rich habitats, where they can reach maturity in half that time. Breeding: Occurs in late spring to mid-summer, with mating taking place under water. Most mature females nest every year, some laying two clutches per season. In early summer the eggs are deposited in the nest, which is generally dug in soil, close to a water source, but some females may dig their nests many meters away from the water's edge (some may move as much as 800 m or half a mile away and up to 90 m or 300 ft above the nearest source of water, but most are within 90 m or 300 ft of water). The female usually leaves the water in the evening and may wander far before selecting a nest site, often in an open area of sand or hardpan that is facing southwards. The nest is flask-shaped with an opening of about 5 cm (2 in). Females spend considerable time covering up the nest with soil and adjacent low vegetation, making it difficult to find unless disturbed. The female lays an average of 4-7 eggs (range 1-13) per clutch, which hatch after ~13-17 weeks. |

| Ecology, Habitat and Diet | Habitat: Occur in both permanent and intermittent waters, including marshes, streams, rivers, ponds, and lakes. Favor habitats with large numbers of emergent logs or boulders, where they aggregate to bask. Also bask on top of aquatic vegetation or position. Often overlooked in the wild. Terrestrial habitats are also extremely important since many intermittent ponds can dry up during summer and fall months along the west coast, especially during times of drought. Can spend upwards of 200 days out of water. Have been found more than 1 km away from water. Many overwinter outside of the water, often creating their nest for the year.

Predators: Generally well protected due to hard shell. Several predators threaten A. marmorata, especially hatchlings due to their small size and soft shell. Raccoons, otters, ospreys, and coyotes and the biggest natural threats, and hatchlings have the additional threats of weasels, bullfrogs, and large fish. Diet: Omnivorous. Most of their animal diet includes insects (aquatic insects and larvae), crayfish, and other aquatic invertebrates. Small fish, tadpoles, and frogs are eaten occasionally, and carrion is eaten when available. Plant foods include filamentous algae, lily pads, tule, and cattail roots. |

| Behavior and Locomotion | Possible to observe resident turtles by moving slowly and hiding behind shrubs and trees. Can be encouraged to use artificial basking substrate (rafts) which allows for easy detection of the species in complex habitats. Bask on mats of floating vegetation, floating logs, or on mud banks just above the water's surface. Engage in aquatic basking in warmer climates by moving into the warm thermal environment in or on top of submerged mats of vegetation. |

| Conservation Status and Efforts | Extirpated in Canada (May 2002: Canadian Species at Risk Act). Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List due to habitat destruction (ponds, wetlands, contamination of other water sources), conversion of wetlands to farmlands, water diversions, and urbanization. Listed as endangered in Washington State and protected in Oregon and California. Pet trade has declined over recent years for this turtle. Occasional losses from illegal collection for food by immigrant populations from Asia. Mortality from motor vehicle collisions. Predation from introduced species (e.g. bullfrogs).

Efforts: Commercial harvest or take of western pond turtles has been prohibited in all U.S. states where it is found since the 1980s. The recent increase in stock ponds and other man-made water sources appears to have a positive impact on population numbers and a few "head-start" programs (where the young are raised in captivity until their shells begin to harden and they are less susceptible to predation) claim to have had excellent survivorship rates after being released into the wild. However, re-introduction is limited if the habitat of the species is not protected. |

| Distribution | Originally ranged from northern Baja California, Mexico north to the Puget Sound region of Washington. As of 2007, they have become rare or absent in the Puget Sound area. They have a disjunct distribution in most of the Northwest, and some isolated populations exist in southern Washington. Pond Turtles are now rare in the Willamette Valley north of Eugene, Oregon, but abundance increases south of that city where temperatures are higher. They may be locally common in some streams, rivers and ponds in southern Oregon. A few records are reported east of the Cascade Mountains, but these may have been based on introduced individuals. They range up to 305 m (1,001 ft) in Washington, and to about 915 m (3,002 ft) in Oregon (sea level to 1500 m). They also occur in Uvas Canyon area, Santa Cruz Mts, California, and in the North Bay, and lakes such as Fountaingrove Lake. |

Genus Malaclemys (diamondback terrapins)

Malaclemys belongs to the subfamily Deirochelyinae and has one species, M. terrapin, which has seven subspecies. The Bermuda population has not been assigned a subspecies.

| Etymology | Terrapin from the Algonquin word for turtle (torope). Diamond pattern on carapace. |

|---|---|

| Physical Appearance | Shell: Overall pattern and coloration vary greatly. Usually wider at the back than in the front (appears wedge-shaped from above).

Color: Shell can vary from brown to grey (greyish to nearly blackish carapace). Body can be grey, brown, yellow, or white. All have a unique pattern of wiggly, black markings or spots on their body and head. One of the darkest species of turtle. Size: Greatest sexually dimorphic size disparity found in any North American turtle. Males grow to approximately 13 cm (5.1 in) while females grow to an average of around 19 cm (7.5 in). Largest female on record was just over 23 cm (9.1 in). Specimens from regions that are consistently warmer in temperature tend to be larger than those from cooler areas in the north. Males weigh 300 g (11 oz) on average while females weigh around 500 g (18 oz). Largest females can weigh up to 1000 g (35 oz). Distinguishing features: Tuberculate (knobbed keel). Higher shell with a deeper bridge. Deeper gular notch. Consistently white upper lip. Uniformly colored carapace and plastron. Skull with a long and bony temporal arch. Adaptations to environment: Can survive in varying salinities. Skin is largely impermeable to salt. Have lachrymal salt glands not present in their relatives which are used primarily when the turtle is dehydrated. Can distinguish between drinking water of different salinities. Exhibit unusual and sophisticated behaviors to obtain fresh water, such as drinking the freshwater surface layer that can accumulate on top of saltwater during rainfall and raising their heads into the air with mouths open to catch falling rain drops. Strong swimmers. Large and strongly webbed hind feet but not flippers as sea turtles have. Strong jaws for crushing shells of prey (e.g. clams and snails) like their relatives Graptemys. Females have larger and more muscular jaws than males. |

| Life Cycle | Eggs: Clutches of 4-22 (usually not more than 4-8). Clutch sizes vary latitudinally with average clutch sizes as low as 5.8 eggs/clutch in southern Florida to 10.9 in New York. Are 1-inch long, pinkish-white, oval-shaped, and covered with leathery shells. Hatch in late summer or early fall. Usually hatch in 60-85 days, depending on the temperature and the depth of the nest. Favor females (almost six to one).

Hatchlings: Usually emerge from the nest in August and September but may overwinter in the nest after hatching. Sometimes stay on land in the nesting areas in both fall and spring and may remain terrestrial for much or all of the winter in some places. Freeze tolerant, which may facilitate overwintering on land. Hatchlings have lower salt tolerance than adults (one- and two-year-old terrapins use different habitats than old individuals use). 1-1.5 in long. May spend their first years upstream in creeks. Move back down to nutrient-rish salt marshes as they grow older where there are plenty of nesting sites. Growth: Growth rates, age of maturity, and maximum age are not well known for terrapins in the wild. Males reach sexual maturity before females due to their smaller adult size. Sexual maturity is dependent on size rather than age (in females at least). Estimations of age based on counts of growth rings on the shell are as of yet untested so it is unclear how to determine the ages of wild terrapins. Maturity in males is reached in 2-3 years at around 4.5 inches (110 mm) in length while maturity in females is reached in 6-7 years (8-10 years for northern populations) at around 6.75 inches (171 mm). Mating: Occurs in early spring. Able to produce eggs for several years after a single mating. Courtship has been seen in May and June and is similar to that of the closely related red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta). Females can mate with multiple males and store sperm for years, resulting in some clutches of eggs with more than one father. Temperature dependent sex determination. Females can lay up to three clutches of eggs per year in the wild and up to five clutches per year in captivity. Unknown how often they may skip reproduction so true clutch frequency is unknown. Females may wander considerable distances on land before nesting. Nests are usually laid in sand dunes or scrub vegetation near the ocean in June and July, but nesting may start as early as late April in Florida. Females dig a nest cavity 4-8 inches deep and will quickly abandon a nest attempt if they are disturbed while nesting. Quickly return to the ocean after covering the nest and do not return except to nest again. |

| Ecology, Habitat and Diet | Habitat: Brackish coastal tidal marshes. Spartina (cordgrass) marshes that are flooded at high tide. Also Floridian mangrove swamps. Favor reedy marshes. Can survive in freshwater as well as full-strength ocean water but adults prefer intermediate salinities. Unclear why terrapins do inhabit the upper reaches of rivers within their range, as they tolerate freshwater in captivity. They are possibly limited by distribution of their prey. Live close to shore unlike sea turtles and require freshwater for drinking purposes.

Predators: Nests, hatchlings, and sometimes adults are eaten by raccoons, foxes, rats, and many species of birds, especially crows and gulls. Diet: No competition from other turtles, though snapping turtles do occasionally make use of salt marshes. May eat enough organisms at high densities to have ecosystem-level effects, specially since periwinkle snails have a tendency to overgraze important marsh plants. Diet is not well studied. Data comes from southeastern end of range. Eat shrimp, clams, crabs, mussels, and other marine invertebrates (especially periwinkle snails). Also eat fish, insects, and carrion. Will only eat soft-shelled mollusks and crustaceans because they use the ridges in their jaws to crush prey. |

| Behavior and Locomotion | Tend to live in the same areas for most or all of their lives. Do not make long distance migrations. Many aspects are poorly known because nesting is the only activity that occurs on land. Limited data suggest that terrapins become dormant in the colder months in most of their range in the mud of creeks and marshes. Quick to flee and difficult to observe in the wild. May be possible to observe them basking on or walking between oyster beds and mudflats. Mild-mannered. Excellent swimmers and will head for water if approached. Known to recognize habits in captivity and learn quickly what times people are normally around. Seem very sociable except when their cage is too small. Enjoy basking together (often one on top of the other). |

| Conservation Status and Efforts | In the 1900s the species was once considered a delicacy to eat and was hunted almost to extinction. The numbers also decreased due to the development of coastal areas and, more recently, wounds from the propellers on motorboats. Another common cause of death is the trapping of the turtles under crabbing and lobster nets. Due to this, it is listed as an endangered species in Rhode Island, is considered a threatened species in Massachusetts and is considered a "species of concern" in Georgia, Delaware, Alabama, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Virginia. The diamondback terrapin is listed as a “high priority species” under the South Carolina Wildlife Action Plan. In New Jersey, it was recommended to be listed as a species of Special Concern in 2001. In July 2016, the species was removed from the New Jersey game list and is now listed as non-game with no hunting season. In Connecticut there is no open hunting season for this animal. However, it holds no federal conservation status. The species is classified as Near Threatened by the IUCN due to decreasing population numbers in much of its range.

Threats: The major threats to diamondback terrapins are all associated with humans and probably differ in different parts of their range. People tend to build their cities on ocean coasts near the mouths of large rivers and in doing so they have destroyed many of the huge marshes terrapins inhabited. Nationwide, probably >75% of the salt marshes where terrapins lived have been destroyed or altered. Currently, ocean level rise threatens the remainder. Traps used to catch crabs both commercially and privately have commonly caught and drowned many diamondback terrapins, which can result in male-biased populations and local population declines and even extinctions. When these traps are lost or abandoned (“ghost traps”), they can kill terrapins for many years. Density of predators are often increased because of their association with humans. Predation rates can be extremely high; predation by raccoons on terrapin nests at Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge in New York varied from 92-100% each year from 1998–2008. Terrapins are killed by cars when nesting females cross roads, and mortality can be high enough to seriously impact populations. Terrapins are still harvested for food in some states. Terrapins may be affected (suffocated?) by pollutants such as metals and organic compounds, but this has not been demonstrated in wild populations. Hatchlings can get trapped in tire tracks left by vehicles on the beach, get dehydrated, and die before reaching water. There is an active casual and professional pet trade in terrapins and it is unknown how many are removed from the wild for this purpose. Some people breed the species in captivity and some color variants are considered especially desirable. In Europe, Malaclemys are widely kept as pets, as are many closely related species. Efforts: The Diamondback Terrapin Working Group deals with regional protection issues. There is no national protection except through the Lacey Act, and little international protection. Diamondback terrapins are the only U.S. turtles that inhabit the brackish waters of estuaries, tidal creeks and salt marshes. With a historic range stretching from Massachusetts to Texas, terrapin populations have been severely depleted by land development and other human impacts along the Atlantic coast. Terrapin-excluding devices are available to retrofit crab traps; these reduce the number of terrapins captured while having little or no impact on crab capture rates. In some states (NJ, DE, MD), these devices are required by law. Relationship with humans: In Maryland, diamondback terrapins were so plentiful in the 18th century that slaves protested the excessive use of this food source as their main protein. Late in the 19th century, demand for turtle soup claimed a harvest of 89,150 pounds from Chesapeake Bay in one year. In 1899, terrapin was offered on the dinner menu of Delmonico's Restaurant in New York City as the third most expensive item on the extensive menu. A patron could request either Maryland or Baltimore terrapin at a price of $2.50. Although demand was high, over capture was so high by 1920, the harvest of terrapins reached only 823 pounds for the year. According to the FAA National Wildlife Strike Database, a total of 18 strikes between diamondback terrapins and civil aircraft were reported in the US from 1990 to 2007, none of which caused damage to the aircraft. On July 8, 2009, flights at John F. Kennedy Airport in New York City were delayed for up to one and a half hours as 78 diamondback terrapins had invaded one of the runways. The turtles, which according to airport authorities were believed to have entered the runway in order to nest, were removed and released back into the wild. A similar incident happened on June 29, 2011, when over 150 turtles crossed runway four, closing the runway and disrupting air traffic. Those terrapins were also relocated safely. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey installed a turtle barrier along runway 4L at JFK to reduce the number of terrapins on the runway and encourage them to nest elsewhere. Nevertheless, on June 26, 2014, 86 terrapins made it onto the same runway, as a high tide carried them over the barrier. Their population is controlled by the raccoon population; it has been shown that as the raccoons decrease in number, mating terrapins increase, leading to increased turtle activity at the airport. Diamondback terrapins were heavily harvested for food in colonial America and probably before that by Native Americans. Terrapins were so abundant and easily obtained that slaves and even the Continental Army ate large numbers of them. By 1917, terrapins had become a fashionable delicacy and sold for as much as $5 each. Huge numbers of terrapins were harvested from marshes and marketed in cities. By the early 1900s populations in the northern part of the range were severely depleted and the southern part was greatly reduced as well. As early as 1902 the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries (which later became the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) recognized that terrapin populations were declining and started building large research facilities, centered at the Beaufort, North Carolina Fisheries Laboratory, to investigate methods for captive breeding terrapins for food. People tried (unsuccessfully) to establish them in many other locations, including San Francisco. |

| Distribution | The very narrow strip of coastal habitats on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the United States, from as far north as Cape Cod, Massachusetts to the southern tip of Florida and around the Gulf Coast to Texas. A population of terrapins on Bermuda has been determined to be self-established (not introduced by humans). |

| Miscellaneous Information | Maryland named the diamondback terrapin its official state reptile in 1994. The University of Maryland, College Park has used the species as its nickname (the Maryland Terrapins) and mascot (Testudo) since 1933, and the school newspaper has been named The Diamondback since 1921. The athletic teams are often referred to as "Terps" for short. The terrapin has also been a symbol of the Grateful Dead because of their song "Terrapin Station". Many images of the terrapin dancing with a tambourine appear on posters, T-shirts and other places in Grateful Dead memorabilia. |

Genus Graptemys (map turtles)

Graptemys belongs to the subfamily Deirochelyinae and comprises 13 species and 15 taxa.

| Alternate names | Sawback turtles |

|---|---|

| Etymology | Sawback because the keel can result in vertebral spines in some southern species. Map-like markings on carapace. |

| Physical Appearance | Has a keel that runs the length of the carapace through the center. Intricate head markings. Strong sexual dimorphism (mature females are twice the length and 10 times the mass as mature males). Females can be split into three groups (while males do not fit neatly with differences in head width not influencing diet).

Microcephalic females: Narrow headed. Sympatric (occur in same place) with a broader headed species. Consume few mollusks. Include yellow-blotched map turtles (G. flavimaculata), black-knobbed map turtles (G. nigrinoda), ringed map turtles (G. oculifera), Quachita/Sabine map turtles (G. ouachitensis ouachitensis and G. o. sabinensis). Mesocephalic females: Moderately broad heads. Tend to eat mostly mollusks along with soft bodied prey. Include Cagle's map turtles (G. caglei), northern/common map turtles (G. geographica), false/Mississippi map turtles (G. pseudogeographica pseudogeographica and G. p. kohni), and Texas map turtles (G. versa). Megacephalic females: Exceptionally broad heads. Feed almost exclusively on mollusks. Include Barbour's map turtles (G. barbouri), Escambia map turtles (G. ernsti), Pascagoula map turtles (G. gibbonsi), Pearl River map turtles (G. pearlensis), and Alabama map turtles (G. pulchra). Common map turtles: Females are 18-27 cm (7-10.5 in), and males are 9-17 cm (3.5-6.5 in). Light markings that resemble waterways on a map or chart. Lines on the carapace are a shade of yellow or orange and are surrounded by dark borders. Rest of carapace is olive or grayish brown. Markings on older turtles may be barely visible because of darker pigment. Carapace is broad with moderately low keel. Hind of carapace is slightly scalloped shaped due to scutes. Plastron is plain yellowish. Head, neck, and limbs are dark olive, brown, or black with thin yellow, green, or orangish stripes. Oval spot located behind the eye off most specimens. Sexual dimorphism in size and shape. Males have a more oval carapace with a more distinct keel, a narrow head, longer front claws, and a longer and thicker tail. Males also have a cloaca that opens beyond the edge of the carapace whereas the female's opens up at the carapace. |

| Life Cycle | Average life expectancy ranges from 15-100 years. 5.5 years in captivity.